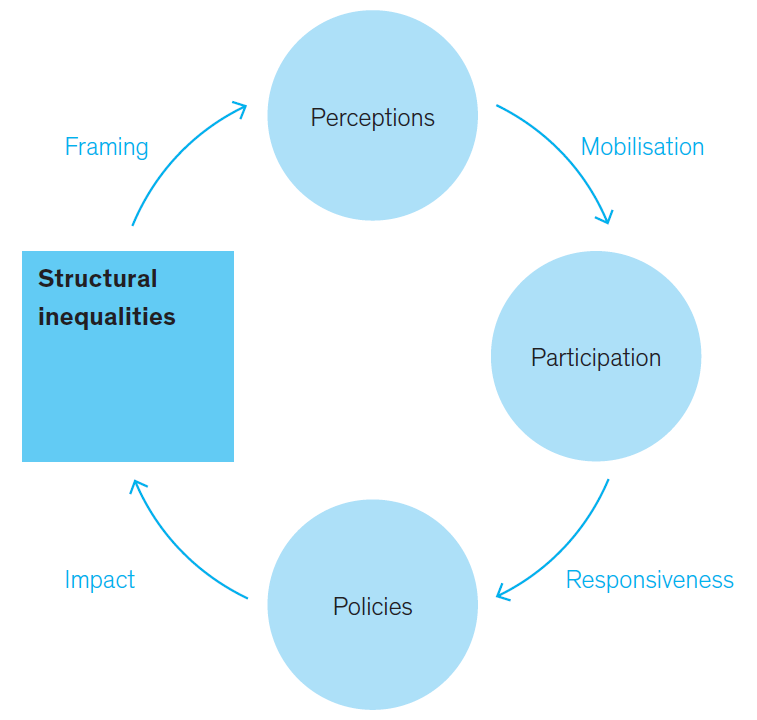

Our approach is most readily summed up in a simple "3 Ps" model: structural inequality is perceived; perception leads to participation; participation leads to policies; these policies, in turn, have an impact on structural inequality. Perception, participation, and policies form a cycle where inequality holds sway at every turn. These are the three research areas in which we engage in our cluster:

RA 1 - Perceptions - Infobox

Research Area 1 addresses issues related to people’s awareness of inequality, to how their awareness affects the preferences they form, and to the role of framing in this process.

Unequally distributed income and wealth, unequal access to information and education, unequal treatment due to group membership: these are the fields in which we investigate the political dimension of inequality. But not every difference in income is perceived as unfair. Likewise, the exclusion of members of a group from certain privileges can be perceived as right and just, even by members of the affected group.

The political dimension of inequality rests on perceptions of inequality. Impulses to change the prevalent order can only flourish where things are perceived, not only as unequal, but as unfair, unjustified, unbearable. So our research must necessarily start with the question:

Why do people perceive some distributions of resources as unfair, and not others – and how does this perception influence their political preferences?

This question is the foundation of Research Area 1: the analysis of perceptions and political preferences regarding inequality. Faced with a given distribution of resources, individuals estimate their own position: am I poor or rich? Uneducated or highly trained? Privileged or oppressed?

We expect that such self-estimates will deviate substantially from actual distributions, as they are often biased. For example, rich citizens often underestimate their position in the income distribution, while poorer citizens believe themselves to be better off than they actually are. Individual perceptions are likely to be affected by the social and political context. Political elites and the media contribute to misperceptions about inequality by highlighting certain aspects of these distributions and omitting others. Language plays an important role in shaping both perceptions of inequality, but also people’s political preferences.

In this Research Area, we study the processes that link inequality, perceptions thereof and preferences for (or against) policies related to redistribution. We especially focus on the effects of framing and filtered information on perceptions of individual positions, and on their role in the formation of political preference. Research Area 1 – Perceptions therefore brings together scholars from different disciplines, including linguists, whose expertise has been missing in social science research about perceptions of inequality and preference formation.

RA 2 - Participation - Infobox

In Research Area 2, we investigate why perceptions of unfair distributions often fail to lead to political participation and mobilisation necessary to change them.

Movements to alter unequal distributions of wealth or privilege are not guaranteed to form – even if things as they are are perceived as unfair and wrong. Sometimes, these perceived problems remain under the action threshold; at other times, protests lose steam along the way, or fail to get the attention of political decision-makers. Merely recognizing that there is a problem, even where it results in strong preferences, does not necessarily result in changes, as well. Change requires political participation: individuals with an opinion must become actors. Political participation requires moving from wanting something to taking action to get it.

Overcoming the collective action problem may be particularly challenging in the field of inequality. Rising inequality might well increase the number of individuals of lower socioeconomic status who are in favour of more redistribution; at the same time, however, this group is less likely to articulate its preferences and to challenge the authorities. This is where our second research question comes in:

Under what conditions do public demands manifest in terms of political action and participation at the individual, group and collective levels?

In this Research Area, we investigate participation and mobilization and their success conditions. Individual resources and opportunities are decisive factors here, and they in turn depend mostly on structural factors. Obiously, opportunities for participation are much reduced in nondemocratic societies, as opposed to true democracies. But in democracies themselves, there are often great differences in the ways political institutions influence the individuals' preference aggregation.

While the inclination to become politically active varies according to the level of education, income and legal status, the mobilization of former non-voters, who contributed to the success of populist candidates and parties in the US and Europe, reveals the complexity of mobilization: not only economic deprivation but also perceived losses of power and influence may fuel populist reactions.

This Research Area looks into the effects of unequally distributed resources and opportunity structures on participation and mobilization. In studying the mechanisms that lead to political mobilisation against inequality, we focus on conventional and non-conventional forms of engagement, including violent ones, in democratic and non-democratic contexts. We also examine the role of social media and new communication channels and determine if they render participation of the disadvantaged more likely, or simply reinforce apathy among those already silent.

RA 3 - Policies - Infobox

In Research Area 3, we study which voices are most likely to be heard in the political arena, and which political responses they trigger.

Simple models of democracy often assume that political interests compete, and the political system responds by generating policies. Policy generation is based on a more or less simple principle of cause and effect. We, however, expect that actors create policies based on citizens’ demands selectively. Obviously, policy-makers are limited in the number of topics that they can address and thereby must be selective. At the same time, some groups are more present in the political arena and some interests better organised than others. Politicians are often more responsive to the wishes of these groups.

This kind of selectivity is most obvious in nondemocratic societies, but democracies also show subtle yet powerful differences in responsiveness. For instance, the legislative might respond more easily to demands made by lobby groups or affluent citizens than by the general populace, thereby translating economic power into political influence. By covering a broad range of different political systems from democracies to autocracies, we investigate why selectivity of policy responses differs widely across these systems.

Unequal responsiveness influences the way in which the political system approaches existing inequality. This is where our third research question comes in:

To what extent do policy-makers respond to different forms of political demands, and how do these political and policy responses in turn affect perceptions, preferences and political participation as well as structural inequality?

In this research area, we investigate the make-up and causes of unequal policy-making in different institutional contexts. When policies respond unequally to existing inequalities, and their responsiveness in turn depends on those same inequalities, powerful feedback loops are established. These can even result in growing inequality in a society. We therefore examine the consequences of these political responses, most importantly as regards their impact on the level of structural inequalities.

At the same time, however, political responses may again shape individual perceptions, preferences and patterns of participation, encouraging or discouraging further political mobilisation. These policy feedback processes need to be taken into account in order to arrive at a comprehensive understanding of the links between inequality and political processes.