Social interactions of female and male Montagu’s Harrier in Spain

How ICARUS tags revolutionize research possibilities

The migratory raptor, Montagu’s Harrier, lives in colonies while breeding in the north, where individuals usually return to the same site as in previous years. During winter, individuals of the same colony might be separated south of the Sahelian region by thousands of kilometres. The research team led by C. Giovanni Galizia, Brigitte Geiger, and Ajayrama Kumaraswamy studied a colony in Extremadura, Spain. “In previous studies, we tagged females and males with GPS-GSM devices to study their movements and social interactions within Spain during pre-breeding, breeding and post-breeding,” explains Galizia. Naturally, they first asked themselves:

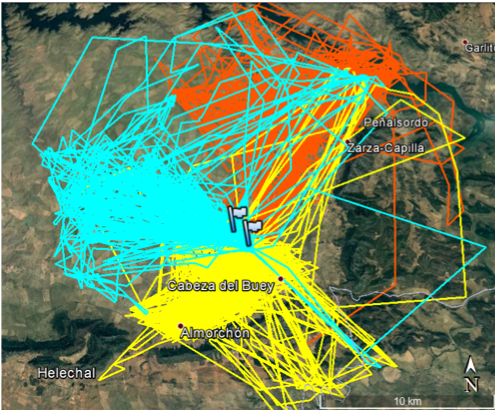

How do individuals interact, both within a colony and with other colonies? Galizia is still overwhelmed by the results: “For the first time, we could show that females, after breeding or after nesting, took off to places occupied by other colonies of Montagu’s Harrier 90 – 270 kilometres away to spend up to 80 days there before starting migration. Males remained at the breeding site until migration started.” Biological fieldwork was necessary to tag the animals. And finally, state-of-the-art computer science is used to handle the huge amount of data created by the tags.

Several questions remained. Galizia comments: “We did not know – so far – how the breeding area related to the place of birth.” Second, they were interested in how females and males disperse in relation to their parental colony. “In the new project, we tagged juvenile birds with ICARUS tags,” says Galizia. “These tags are lighter than the previous tags we used, thus allowing us to tag juveniles. In this way, we will be able to investigate our research interest.” That was only possible because of new techniques: Special tags were developed that communicate with the ICARUS team via the ISS.

Juveniles could be tagged for the first time

The innovative character of the latest campaign is twofold: The ICARUS tags are still in an experimental phase, and their usage with different species is an important aspect in developing them further. On a biological side, it is probably the first time that researchers could deploy tags that are lightweight enough to allow for juveniles to be tagged.

Even though the results are already fascinating, there is still a lot to explore: “We would like to follow more fledglings in order to find out about dispersal – also to see whether fledglings tagged at the end of the season try to disperse within Spain or start migration from the nesting site.” They therefore need to tag more juveniles, in particular juveniles that hatch later in the year, which are reported to have less likelihood of survival.

Copyright: Giovanni Galizia